Thirteen years ago, the Oculus Kickstarter launched modern VR. Eye tracking was a dreamy footnote.

Today, in 2025, eye tracking is built into most premium HMDs: Vision Pro, Galaxy XR, Quest Pro, PSVR2, Varjo XR-4, Play For Dream MR, and others. Sub-degree accuracy, foveated rendering, and gaze menus are finally shipping.

But, like… what’s it for?

The Current Reality

- Saves GPU cycles

- CAN foveate the frustum IF developers ever use it

- Makes avatars less dead-eyed

- Lets you “look to select” in tidy demos

That last one is the one that most interests me. I’m obsessed with finding the correct interaction model for XR. We haven’t found it yet, and I believe eye-tracking is a big chapter along our quest.

The HCI Hype Train

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves though.

Research is abuzz with papers (often commissioned by HMD OEMs) claiming eye tracking is the killer interaction model for spatial computing, but recent work like Liu et al.’s “Enhancing Smartphone Eye Tracking with Cursor-Based Interactive Implicit Calibration” (CHI 2025) shows yet again that even with significant improvements, gaze-based control still requires calibration and doesn’t match the precision of traditional input methods like mouse cursors.

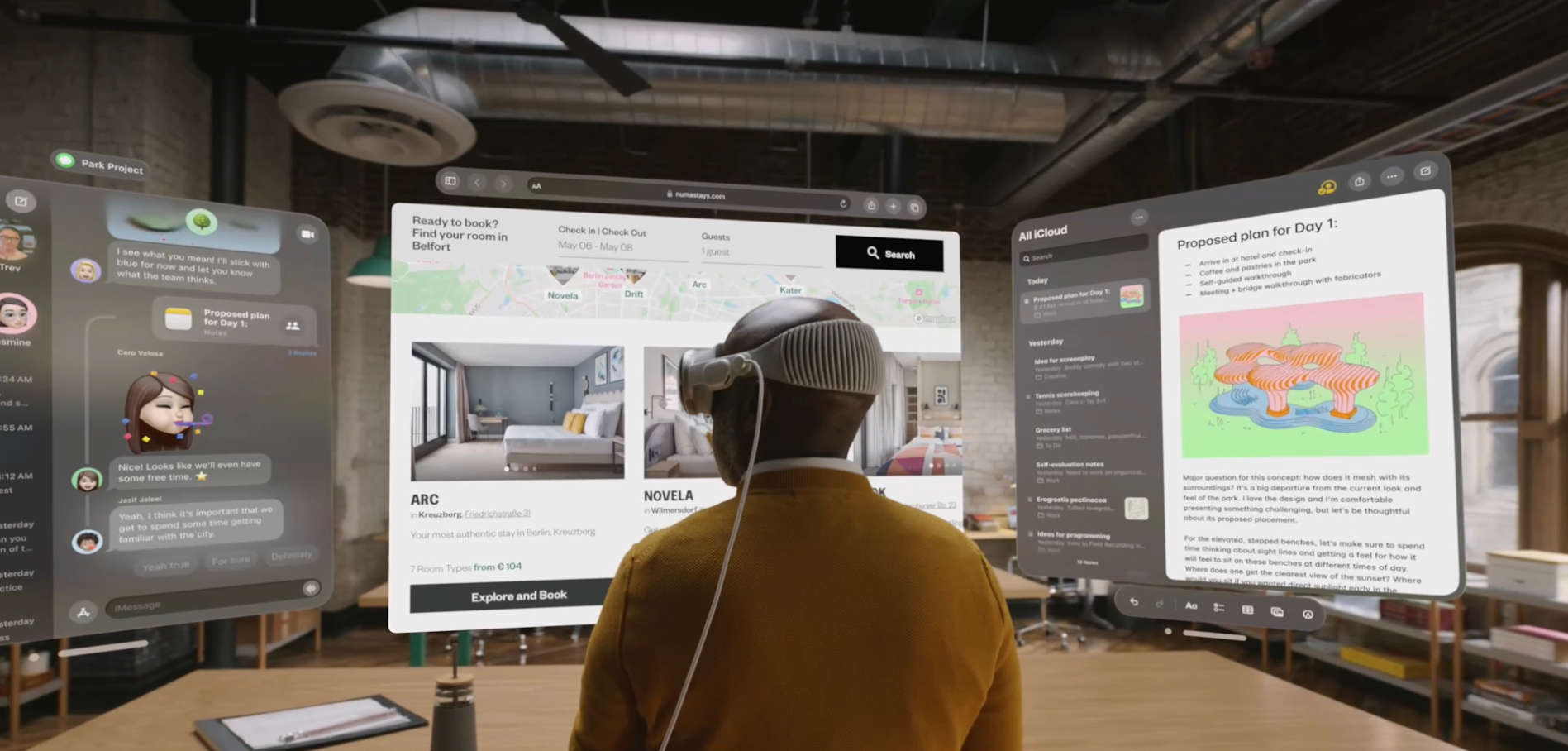

Still, the XR community was excited enough to convince Apple that their fist swing at dedicated spatial computing in Vision Pro 1.0 should utilize eye tracking as a core component of its entire interface.

This was an overzealous move in my option, but I get it. They have and instinct that there’s a there there, and I think they’re right. The problem? They were trying to build an airplane with stone tools. We’re not ready for eye tracking yet.

Gaze alone is high-intuition, low-fidelity. Great for rapid ballpark selection, terrible for fine control, not to mention eye fatigue has always been an ergo concern likely to escalate if we start building a lot of UIs that require gaze to fixate on tight local elements. Eye tracking isn’t the final answer—but I do believe it’s a vital ingredient. It’s a piece to the puzzle that needs the other pieces in place before it can shine.

The Other Pieces: Near Field vs. Far Field

Everything within arm’s reach feels effortless. Everything outside our reach feels like casting a fishing line with a toy rod. I recently wrote a post called Why I Hate VR Raycasting As An Interaction Model. It’s a treatise on what NOT to do in an XR interface. I’d never say “never use raycasting,” but I will stand firm on “almost never use raycasting.”

After years in XR, I believe the final interaction model that will define the universal operating system of XR will be built on a triple-proxy setup as its linchpin, instead of our modern day crtuch, the raycast cursor. Eye-tracking will not come into its value until this piece of the puzzle is resolved. The resolution requires triple-proxy IO.

Who shot who in the triple-proxy what-now?

Triple-proxy capability is the missing core of XR UX. To fully define it, we need to trace its roots in video games and operating systems.

Almost every GUI seeks to establish interaction between the user and a content object. In video games, these nuts and bolts are called MVP:

MODEL - the spatial reference frame of the digital object

VIEW - the spatial reference frame of the user’s perspective

PROJECTION - a mapping of MODEL to VIEW for rendering to a 2D screen using a 3rd reference frame, a “world space” in which both virtually exist in a shared frame

We can think of any WIMP UI in similar terms:

ICON (I in WIMP) the interactable thing, like the model

WINDOW (W in WIMP) the view

POINTER (P in WIMP) input instead of output

Instead of rendering via projection (output), UI uses a pointer or cursor to provide input via the same concept of a shared virtual space, a world refernce frame. In the case of 2D operating systems, the shared space is an X/Y canvas where the object takes up a fragment and so do we, the users, via a cursor.

What is the equivalent when we extrapolate WIMP concepts into 3D?

It may be instinctive to think we’ve been “interacting” in 3D games for decades, but gaming never intends to tackle the full challenge I’m targeting here.

In a game, we usually embody a character. That character sometimes has an ability to reach out into the world beyond its body and manipulate other objects in the scene with God-like capabilities, but it’s fairly rare for a character to have a full Turing-complete God mode. That would ruin most games, but in a productivity context, it’s the necessary ingredient we’re missing.

And we do have God-mode in an operating system, but we usually still think of operating systems as 2D? Why? Because that’s what they’ve been in 99.9% of the examples we’ve seen. It’s not that we can’t conceive of a 3D operating system. It’s just that, every time we do, we tend to fall back on that crutch of raycast, which is really just us trying to square-peg our familiar 2D mouse interaction model into the round hole of VR.

The user has full 6DOF head tracking and hand tracking. Raycast so heavily restricts the full simultaneous use of all these DOFs that it must keep begging the question until we answer:

What Would Jean Grey Do?

How can we get at the goal of manipulating ANYTHING in the far field the way Jean Grey does? She doesn’t cast a fishing line and swing objects in an arc around her body. No. She thinks a thought… doesn’t need to lift a finger. She wills a thing to move from wherever it is… to wherever she wants it, in a straight line, in any direction in 3D, with unifrom precision, fast or slow, her choice.

We need triple-proxy capability to become Jean Grey. She has a mental model of the physical world around her. We don’t. We have a visual model (coming back around the bend to eye tracking soon, I promise). Therefore, we need to manifest her mental model visually, with proxies for 1) the object, 2) for ourselves, and 3) for the world. Sounds familiar, I hope.

-

Proxy the user out

Raycast is not a 1-to-1 hand/cursor proxy. If you want to be able to place a cursor with equal precision anywhere in the visible field, raycast won’t do it. Instead, we need a 1-to-1 hand/cursor proxy that moves with 3DOFs of translation. Raycast turns your hand’s 3D motion in an X/Y coordinate system to ape mouse movement. It’s a backwards-compatibility tool for a 2D mouse, yet we use it as the default far-field interface in XR. Lame. What we SHOULD do is send a full 3D proxy into the far field that can match 3D hand motion. This is a primary component of Jean Grey’s mental model. She can manipulate that thing because some aspect of her will goes out there and possesses it. Whatever that looks like in her mind’s eye, we need to see that rendered in our viewport. It’s just like rendering a digital double of your hand in VR, except… it’s over there. Maybe it’s a full hand model. Maybe it’s just a dot, or anything in between. But it MOVES just like your hand, one-to-one, or with some kind of multiplier.

-

Proxy objects in

Why did we send your hand over there? Because there’s at least one interactable object over there and we don’t want you to have to walk over to it. Jean Grey never needs to walk over there. That would be grossly inefficient from a productivity standpoint, quite opposite to the experiential value of presence in most video game narratives. In addition to creating a proxy of your hand “over there,” we also need to proxy the object “over here.” It’s a tried-and-true XR HCI research technique called voodoo-dolling. A voodoo-doll version of the object appears within reach, marrying the near-field and far field temporarily.

-

Proxy entire worldspace zones

In video game rendering and in 2D operating systems, we have the user, the object, and world. In our two-way proxy setup, we have the user, the object, and… we need to proxy the world too. There might not be just one interactable object out there. There might be hundreds. We need instantaneous proxy access to some/all of them.

Once we’ve seen enough examples of triple-proxy capability in action, I believe it will come to be seen as table-stakes for efficient UI and UX in all XR operating systems. The obvious way we need to design an operating system for spatial computing platforms is the way that gives us God-mode, A.K.A. Jean Grey’s 3D transformation powers. It’s just silly on its face not to expose triple-proxy capability to the user at the OS level.

The Mouse of XR?

Just like there’s not a mouse cursor in every app, you won’t be required to use a triple proxy interface for any given VR game or experience, but it should always be available when navigating the base layer of an XR operating system. It is the true mouse of XR. Raycasting is not the mouse of XR. Raycasting is the mouse of PCs… in XR.

Wasn’t this a post about Hand Tracking

Let’s tie it all together. Why does hand tracking matter for a triple-proxy setup?

Triple-proxy capability doesn’t necessarily handle hover and selection out of the box. In a base case where you assume the ENITRE interactable scene is proxied in near-field reach, you might assume selection becomes 100% near-field interactivity, so there’s no need to gaze out to hover/select.

That’s a short-sighted assumption in my opinion. The entire value of triple-proxy capability could be dashed by requiring the user to gaze for extended periods into the near-field proxy rather that keeping focus on the actual far-field content. What do we want our user looking at in most cases?

I argue we want them looking at the far field by vast majority. The whole point is to let them get all Jean-Grey-ish up in that entire 3D space.

If you have to crane your neck into your lap frequently, it’ll be a double-whammy of bad ergo and value reduction by drawing focus from the very powerful metaphor of levitating giant objects with your mind. Grabbing the voodoo-doll is like playing with a toy if you’re only paying attention to that part. It would be like staring at your fingers during touch-typing or staring at the XBox controller instead of your game screen.

So if your gaze is mostly on the far field, and the vooddo doll widgets are mostly intended for peripheral feedback, how do you select things again?

Eye tracking.

Eye tracking is the jelly to triple-proxy God-mode’s peanut butter. I don’t know the perfect implementation of it. I can picture 100 prototypes that hack at this concept from 100 different angles.

I published a very green pre-alpha Unity project called Atomic back in 2020 which revealed the full nature of this challenge to me. It was a project originally meant as a nameless node-based visual programming language, but it never got far because node clouds in XR are impossible to use without triple-proxy capabilities, and I sorely lacked awareness of this at the time of the project’s creation.

That’s why it turned from a VPL prototype into a triple-proxy XR transform gizmo prototype pretty quickly. It has gizmo widgets (akin to voodoo dolling) that I think are a pretty good first crack at triple-proxy capability, but it’s a devastatingly basic attempt, and I haven’t had time to touch it for years. And I had no access to eye tracking hardware back then.

Neither triple-proxy nor eye tracking can stand alone in XR. United, they’re strong. This is UX fruit that has been low-hanging ever since eye tracking HMDs started launching. I’ve zero time to prototype in this direction, but I SO desperately want to unshelve Atomic when there’s a free moment of not hawking my wares as a contract XR dev.

So that begs the final question: which of you XR devs is going to beat me to this low-hanging fruit?

AJ Campbell,

Tech Lead/Senior XR Programmer Guy

GitHub: https://github.com/ajcampbell1333

Portfolio: https://ajcampbell.info